Warren Buffett once referred to derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction.”

He wasn’t being dramatic—he was warning that if things went wrong, these complex financial instruments could cause massive, far-reaching damage to the global economy. What Buffett feared most was how a sudden, unexpected market shock could set off a dangerous chain reaction through the financial system, fueled by the hidden risks and tangled interconnections that derivatives create.

These instruments link major banks, hedge funds, and corporations in an intricate web of bets on the future prices of , , currencies, and more.

For example, airlines and energy companies routinely use oil-linked derivatives to hedge or speculate. If oil prices were to surge unexpectedly, the counterparties on the losing end—often large financial institutions—would be on the hook for enormous payouts. That, in turn, would trigger margin calls, liquidity crunches, and potentially forced asset sales.

The fear spreads quickly, because many of these derivative contracts are opaque—no one really knows who is exposed or by how much. That uncertainty can lead to panic in the markets, as everyone starts pulling back at once.

Losses like these rarely stay contained. A default in one part of the system spreads risk outward. If a major player can’t cover its exposure, it endangers its counterparties. If one of those is a major bank, the problem quickly becomes systemic.

This is precisely the kind of domino effect Buffett was describing—a market shock lighting fuses in unexpected places, turning financial interconnectivity into financial fragility.

Because derivatives are so interconnected and can involve huge sums of money, the damage can grow quickly and unpredictably, much like a series of explosions. That’s why Buffett saw them not just as risky tools, but as potential threats to the entire financial system. In other words, financial WMD.

So why bring this up now?

Because the recent war between Israel, the US, and Iran is far from over. At some point, a far more serious confrontation between the US and Iran appears inevitable—and when it comes, it will almost certainly disrupt the flow of oil and gas from the Persian Gulf.

To call that a severe supply disruption would be an understatement.

Consider this.

The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow strip of water that links the Persian Gulf to the rest of the world.

It’s the world’s single-most important energy corridor, and there’s no alternative route.

Five of the world’s top 10 oil-producing countries—Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait—border the Persian Gulf, as does Qatar, the world’s largest exporter of liquefied (LNG).

The Strait of Hormuz is their only sea route to the open ocean… and world markets.

At its narrowest point, the space available for shipping lanes in the Strait of Hormuz is just 3.2 kilometers wide.

According to the US , around 20 million barrels of oil transit the Strait daily, accounting for roughly 20% of global oil production—worth about $1.4 billion per day at current prices. Another 20% of global LNG exports also move through the Strait.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Strait of Hormuz to the global economy. If someone were to disrupt the Strait, it would ignite a full-blown energy crisis, sending prices soaring and financial markets into chaos.

Thanks to its commanding geography and expertise in unconventional and asymmetric warfare, Iran can shut down the Strait, and there’s not much anyone can do about it. It’s Iran’s geopolitical trump card.

Analysts believe it could take weeks to reopen, if at all. Pentagon war games have shown that in a full-scale war, the US Navy would be unable to keep the Strait open. Faced with swarming missile attacks, American forces would either have to withdraw or risk total annihilation.

Worse still, Iran could target oil infrastructure across the Persian Gulf, destroying production facilities in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. Even if the Strait reopened, there could be nothing left to export.

Military strategists have known this for decades, yet no viable strategy has ever emerged to neutralize Iran’s leverage. Tehran has made it clear: if a full-scale war breaks out, it will close the Strait and destroy the Persian Gulf’s energy infrastructure.

In short, Iran holds a knife to the throat of the global economy.

Since the 1979 Revolution, the US has sought to overthrow Iran’s government. But Iran’s control over the Strait has long served as a powerful deterrent to regime change. That deterrence, however, may be breaking down.

We are now in the midst of World War 3—and Iran has become the decisive battleground. The US and Israel may be willing to risk global economic collapse to topple the Iranian government, a move that would dramatically shift the global balance of power in their favor.

If a war with Iran shuts down the Strait of Hormuz, the impact would dwarf every oil crisis in modern history.

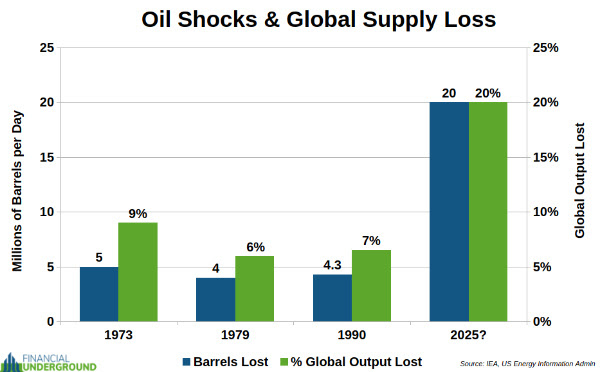

During the first oil shock in 1973, about 5 million barrels were removed from the global oil market. At the time, daily global oil production was around 56 million barrels. That means roughly 9% of the world’s supply vanished.

Oil prices roughly quadrupled.

In the second oil shock of 1979, about 4 million barrels disappeared from the market. Daily production was around 67 million barrels—so about 6% of global supply was lost.

Oil prices nearly tripled.

Then, in 1990, during Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, about 4.3 million barrels were removed. With global production at roughly 66 million barrels per day, that was a 7% supply loss.

Oil prices more than doubled.

Now compare that to a Strait of Hormuz shutdown, which could instantly remove 20 million barrels from a global market producing about 100 million barrels per day—a staggering 20% of supply gone overnight.

This would be the largest supply shock in history. By far.

If war with Iran proceeds and Tehran closes the Strait of Hormuz, I think the effect on the price of oil will be at least as severe as it was during the 1973 oil shock, which saw oil prices go up 4x.

A similar move today could see oil prices above $275 a barrel.

However, I consider that a conservative estimate because closing the Strait of Hormuz would cause a much larger supply shock than the 1973 oil embargo.

And unlike financial crises of the past, this one can’t be fixed with printed money. Central banks can inject liquidity, but they can’t manufacture oil. Physical supply shortages aren’t solvable by monetary policy. Even the combined efforts of the US and Russia to increase oil production couldn’t replace the missing 20 million barrels per day quickly enough to prevent market chaos.

This kind of price shock would hit derivatives markets like a sledgehammer, where oil and gas are heavily traded via futures, options, and swaps. Any firm on the wrong side of the trade would face steep losses, triggering margin calls, liquidity demands, and potential defaults. Big banks that serve as counterparties or intermediaries would be directly exposed to the fallout.

This could set off a cascade of defaults and margin calls that ripple through the global financial system—and make 2008 look tame by comparison.

A closure of the Strait of Hormuz is a credible trigger for a catastrophic global economic depression.

Iran’s true nuclear option isn’t a warhead—it’s a financial WMD, setting off a chain reaction by shutting down the Strait and sending oil prices through the roof, detonating the derivatives bomb at the heart of the global financial system.