It’s Jobs Week. Yesterday was the release of and labor turnover for April. Tomorrow is the unemployment insurance claims for the last week of May, and Friday is the for May. It’s time to test the economic narrative.

Any signs of weakness in the data this week would stoke fears of a recession again. It’s too soon to see the full effects of tariffs, DOGE, or other policies on the labor market; softening now would suggest less resilience to those later effects, raising the odds of a recession.

Three years ago, widespread concerns arose that a recession was inevitable after inflation surged, and the raised rates rapidly in response. The recession didn’t happen. That false signal has some questioning the concerns now about a recession. The risks to the economy in the two episodes differ, and so do the buffers.

The notable strength of the labor market in 2022-23 served as a critical buffer against a recession. It helped offset the drag on growth from higher and higher interest rates, providing time for pandemic-related disruptions to unwind. As today’s post argues, we are not starting with a similarly strong buffer with the labor market.

The labor market being solid or “in balance” now, as opposed to very strong, leaves employment more vulnerable to a decline in demand from tariffs, reduced immigration, and federal government downsizing.

Buffer: Hiring Rates and Rewards.

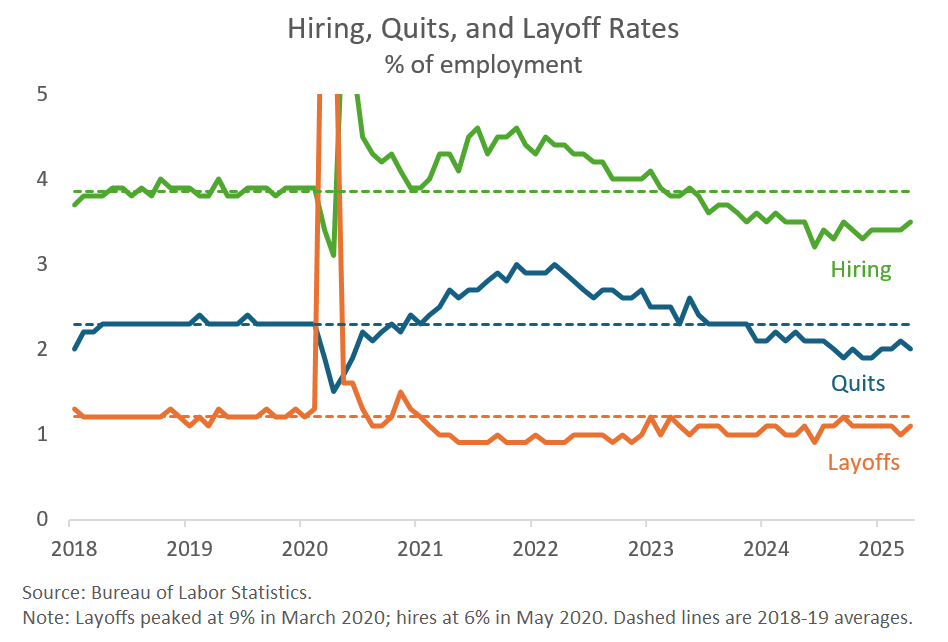

A remarkable feature of the labor market in 2022 was the degree of workers moving into and between jobs. Businesses were hiring (green line) at a substantially higher rate than before the pandemic. Workers were more likely to quit voluntarily (blue line), often moving to a new job, which is another sign of strength. The layoff rate was very low.

The high degree of churn served as a buffer, allowing workers to find new employment quickly, and it also indicated greater bargaining power among them.

Since then, the hiring rate and quit rate have fallen back and are now well below their pre-pandemic averages. (Note, the readings are little changed this year through April.) The decline in the hiring rate has meant it’s harder to find a job. Even without an increase in layoffs, this can put upward pressure on the , as the unemployed tend to stay unemployed for longer periods.

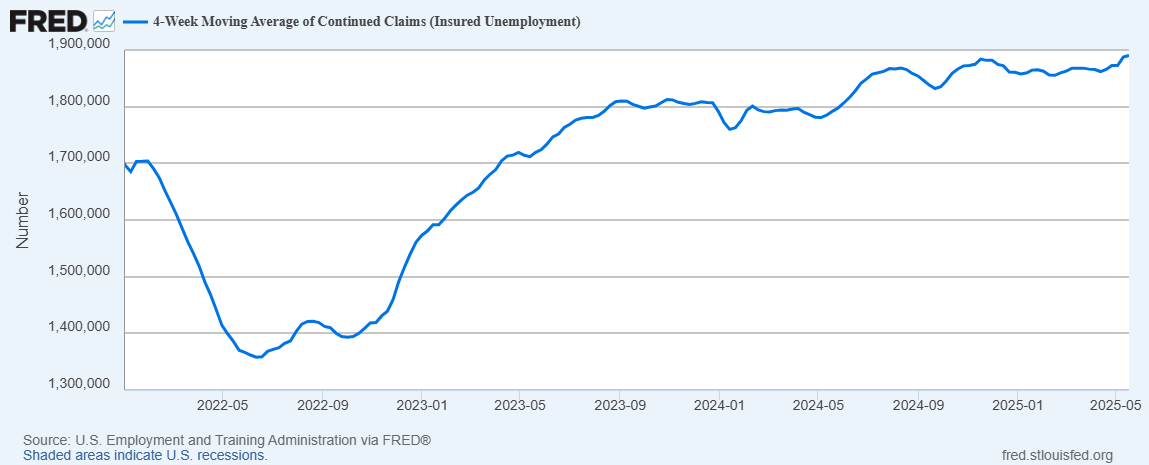

That is consistent with low initial claims for unemployment insurance, but rising . Last week, continuing claims (for the previous week) hit their highest level since 2021.

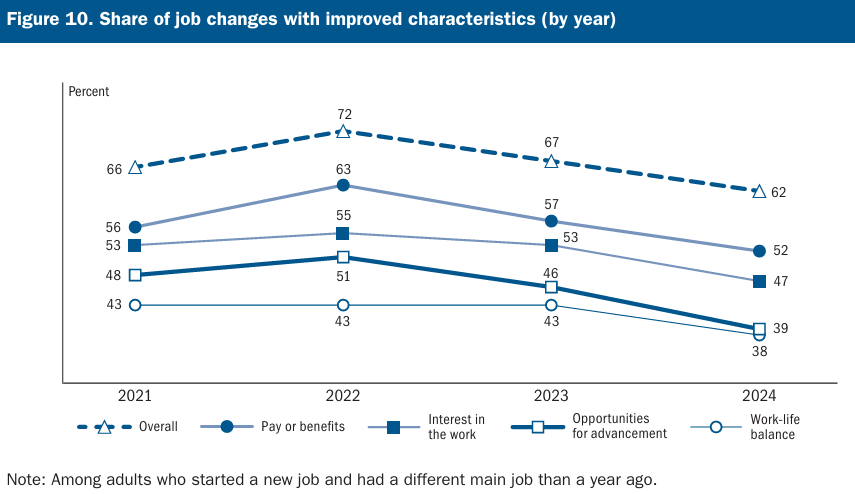

The strong hiring in 2022 offered more than just jobs. The new jobs were also more likely to be better jobs than previous ones. In fall 2022, 72% of workers who had started a new job said that it was a better job than their prior one, according to the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking. That estimate covers workers who had switched jobs at the same employer or moved to a new employer.

By the fall of 2024, that fraction had fallen ten percentage points. Pay or benefits and opportunities for advancement were two categories that saw the largest declines.

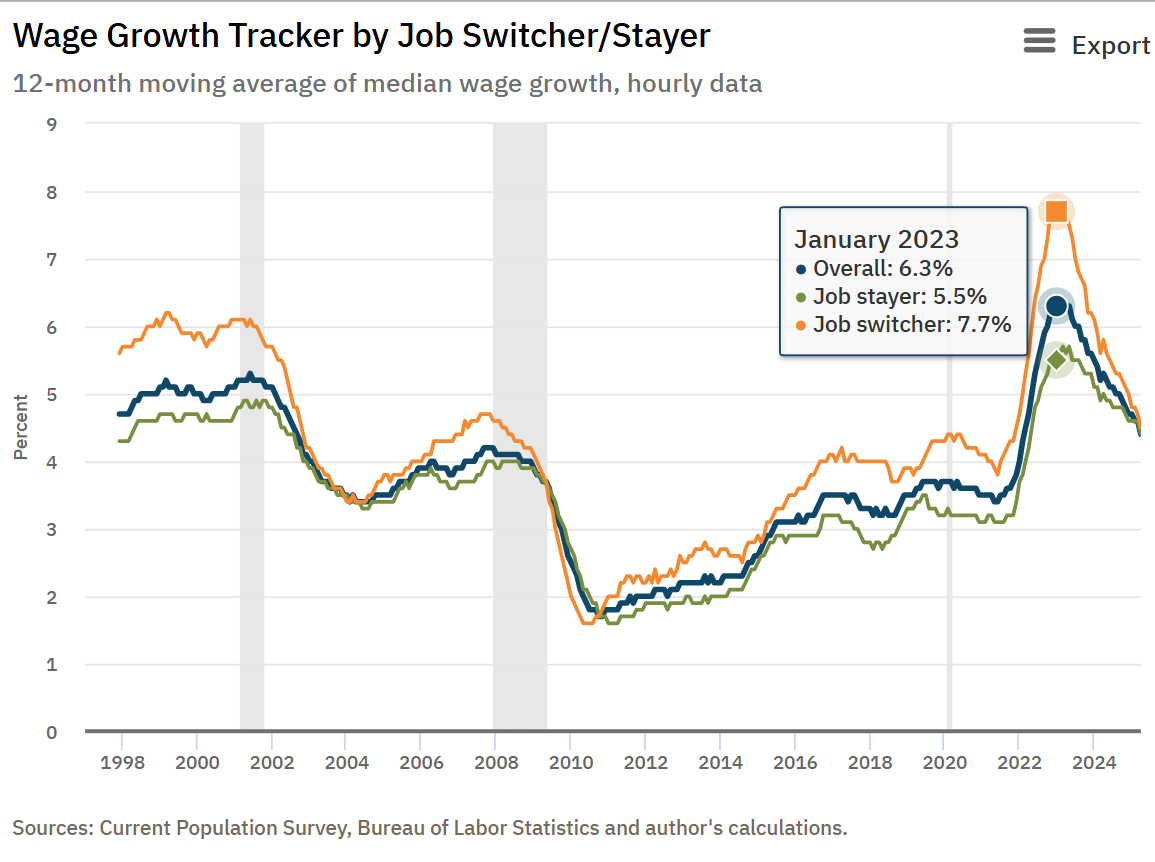

The narrowing wage premium from switching jobs is also evident in the household survey in the employment report. Larger paychecks from switching served as a buffer against the higher inflation in 2022. That is no longer the case. Wage growth is essentially the same for both switchers and stayers.

Buffer: Job Openings.

Fed Governor Chris Waller argued in 2022 that the very strong labor market provided a path for the Fed to cool demand and reduce inflation without substantially rising unemployment. Specifically, in work with Fed economist Andrew Figura, he argued that the elevated vacancy rate offered employers a margin to adjust if demand softened. They could reduce openings, rather than laying off workers.

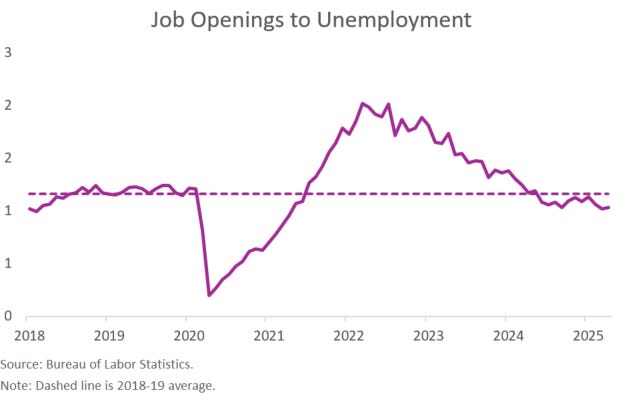

In fact, job openings have decreased by about 40% since the spring of 2022, while the number of unemployed individuals has increased by half as much. Excess job openings were a buffer. Waller, speaking this week, acknowledged that this extra buffer is no longer in place.

We have seen a reduction in wage pressures over recent months, and the ratio of job vacancies to the number of unemployed people has moderated from as high as two a couple of years ago to close to 1 today, which was about where it was before the pandemic. With a balanced labor market, if aggregate demand slows noticeably, businesses are likely to look for ways to cut workers.

Buffer: Breadth of Job Gains.

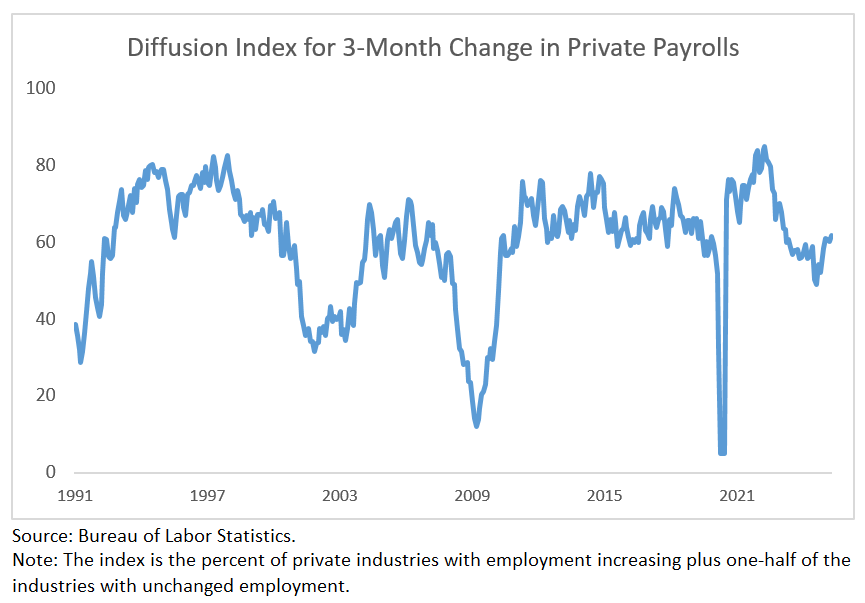

The breadth of the labor market strength was also unusually large in 2022. That’s true whether looking across industries or demographic groups. For example, the diffusion index for three-month employment changes across the 250 private-sector industries reached its highest level since the series began in 1991, in mid-2022.

A reading of 50 represents an equal balance between industries with increasing and decreasing employment. Growth across many industries, as was the case in 2022, offer more resilience to shocks than narrowly-focused growth.

That buffer of exceptional breadth no longer exists. The diffusion index is now close to its pre-pandemic level and at the low end of the range in prior expansions. Even more worrisome is that the current gains in employment are concentrated in areas such as government, healthcare, and private education, which could be directly affected by the federal spending cuts.

In Closing

When considering the chances of a recession this year, it’s essential to understand the shocks we are facing and the buffers in place. This week’s labor market data offer perspective on a key buffer. Along many dimensions, it’s clear that the labor market today will not offer the same buffer as it did in 2022-23.

While that implies less protection from a recession, it may reduce the upside risks to inflation somewhat, as businesses may find it more difficult to pass on tariff-driven costs to consumers than they did pandemic-driven ones. We are in the early stages of observing the effects of the Trump administration’s policies on the economy.

The labor market is not the first place we should expect to see the effects; even so, its resilience now will be critical to the eventual outcomes.