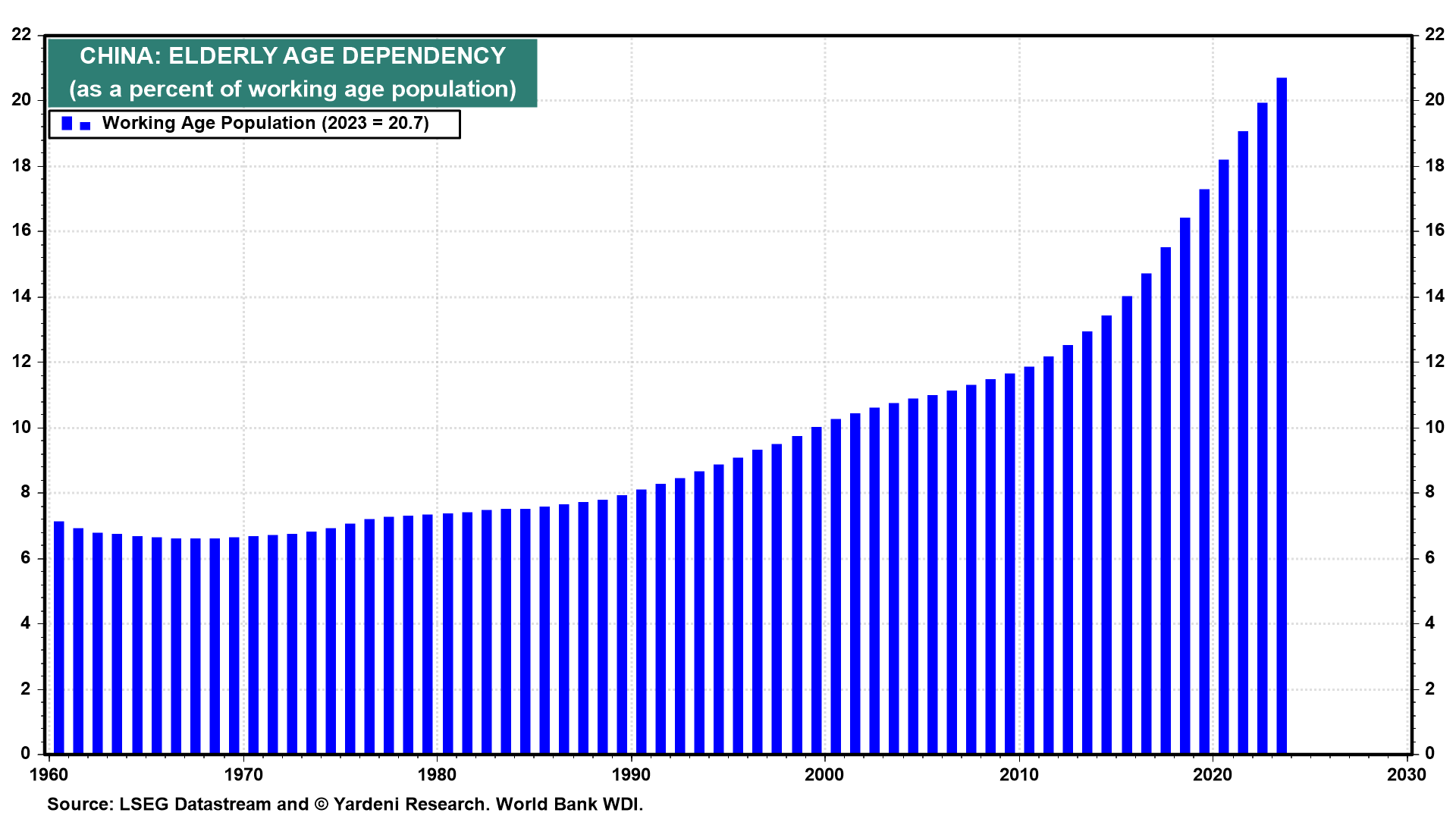

For a decade now, economists have been theorizing about how China’s aging and shrinking population might affect its economic growth potential. Yet there’s nothing conjectural about the ways demographics are now exacerbating the nation’s deflation troubles.

As Japan’s experience since the 1990s has highlighted, few Asians in their mid-60s and higher consume with gusto as twenty- and thirty-somethings do. They tend to buy fewer houses, cars, and appliances; to upgrade technology less frequently; and to splurge less on luxury dining and travel.

Let’s explore how China’s demographic trends are stacking the deck against policymakers as they battle deflation:

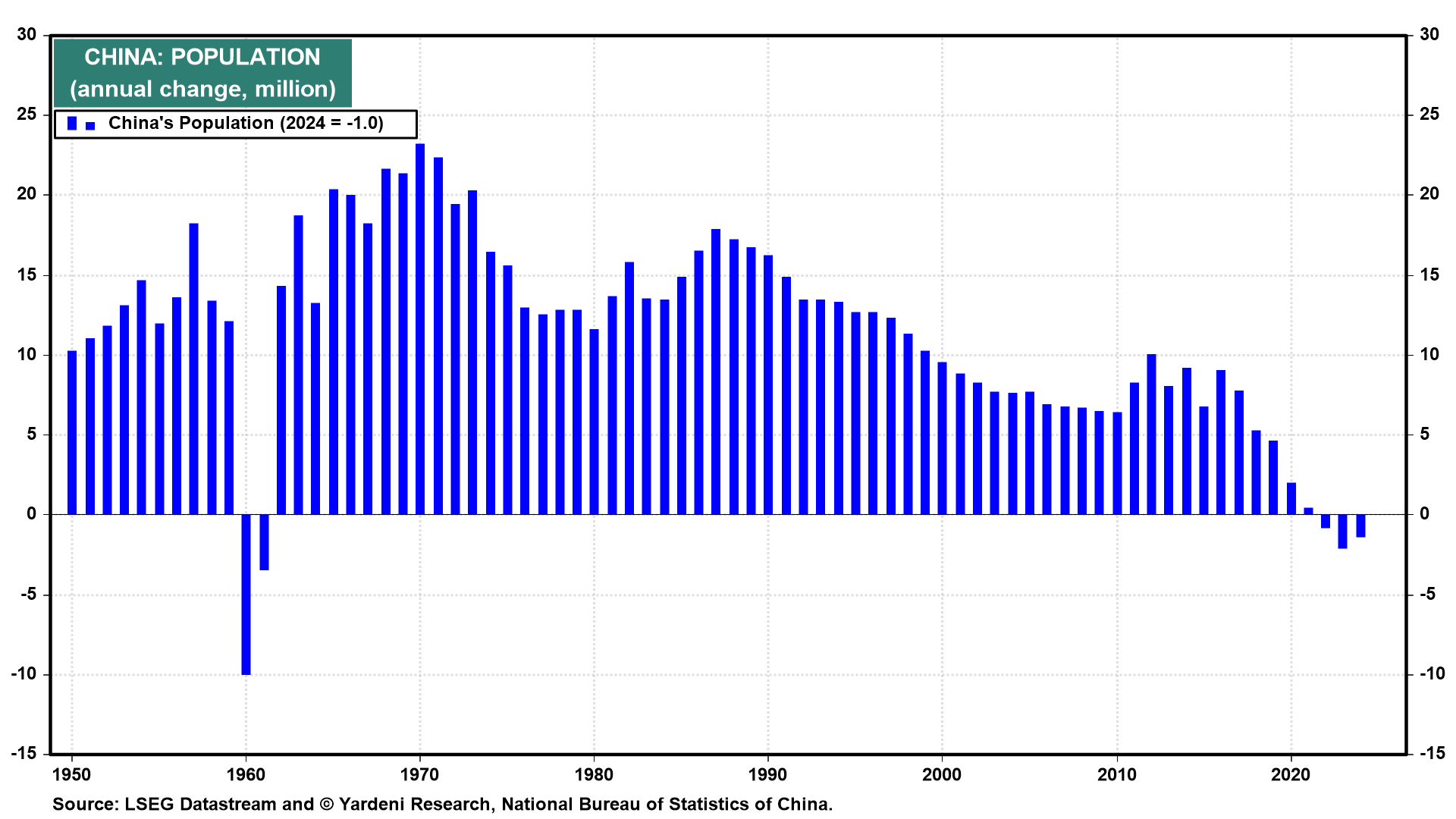

(1) China’s population drop is secular. In 2024, the nation’s population shrank for a third year, falling by 1.39 million y/y to 1.408 billion—an unprecedented trajectory since the country’s founding in 1949. And pressures on the economic system come from both ends of the lifecycle: Elderly Chinese are living longer, straining their pensions, and the birthrate is falling, providing fewer new consumers.

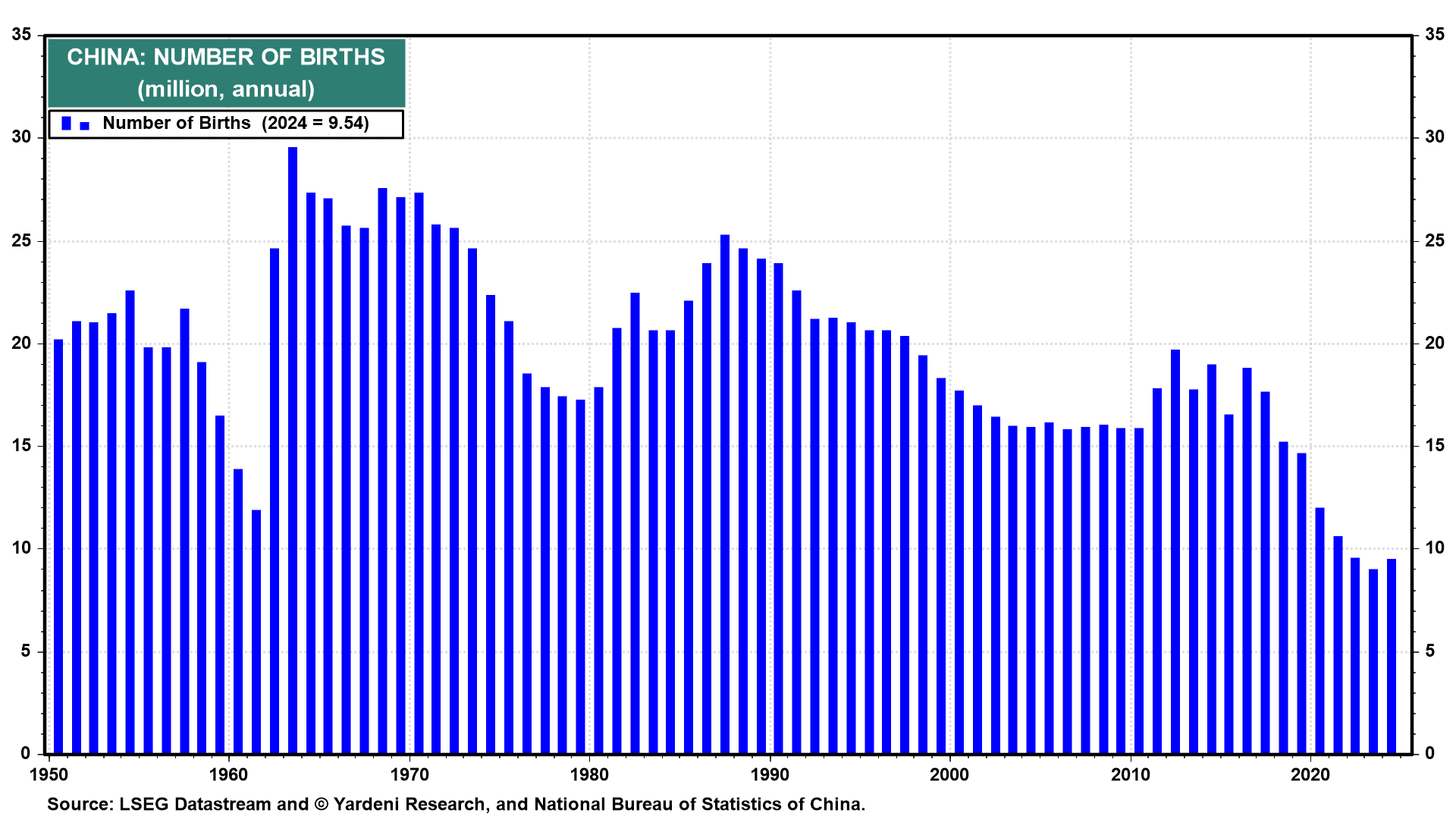

The number of births has been below 10 million since 2022. The United Nations estimates that China’s population will halve to 633 million by the end of the century. Over the next decade, China could lose the equivalent of South Korea’s entire population—50 million-plus—according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

(2) History catches up. As economic own-goals go, Mao Zedong’s draconian “one-child policy” is in a category of its own. At the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1979, Mao’s Communist Party worried that a rapidly growing population would be impossible to feed. Reducing birth rates became a national priority, executed with elaborate measures. By the time President Xi Jinping ended the policy in 2016, it was too late: A policy that dictated the social order for generations has proven hard to overcome.

Today, Chinese households cite rising living costs and career uncertainty for why they’re having fewer babies. Such concerns have younger mainlanders delaying marriage or eschewing it altogether.

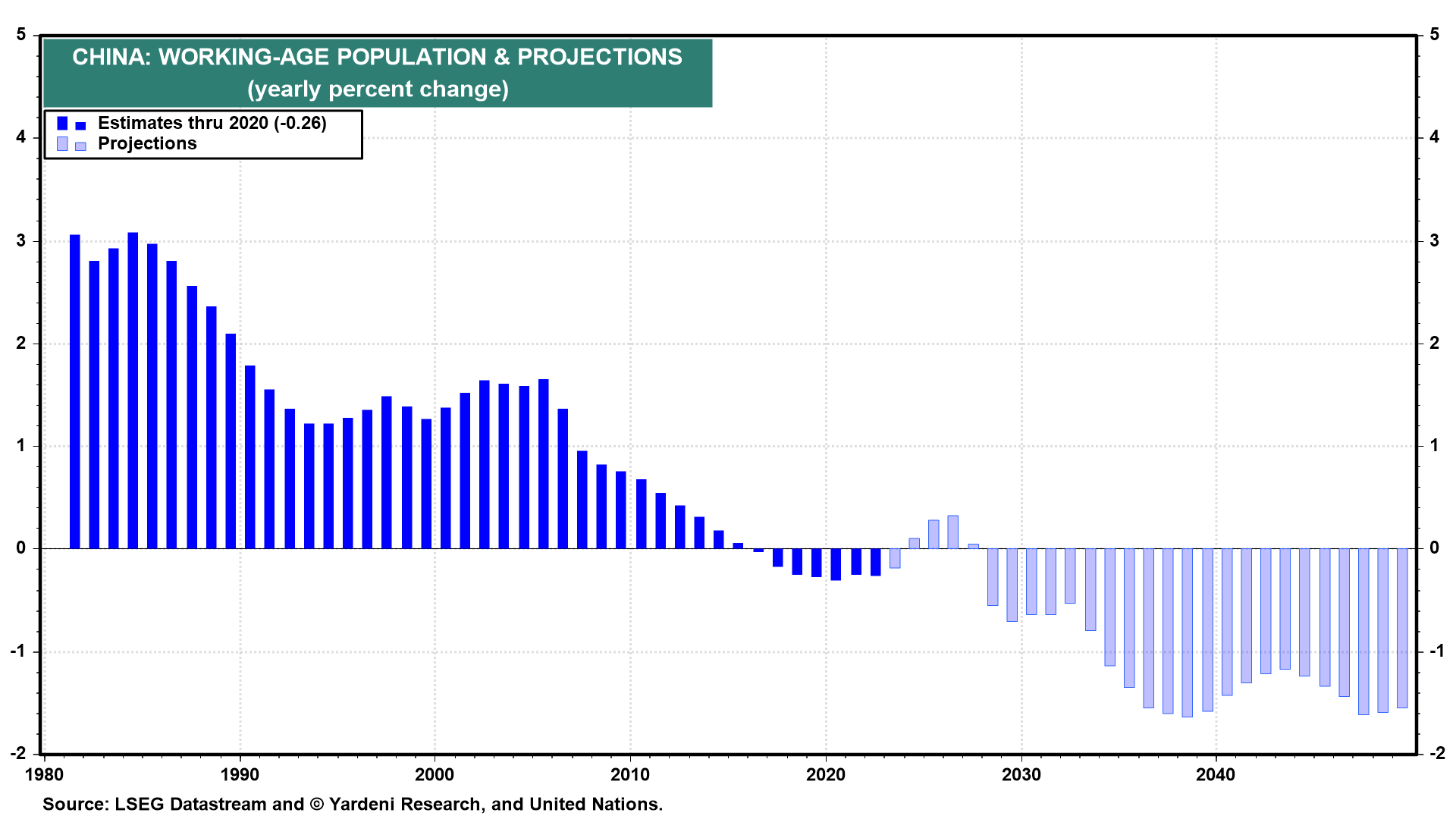

A shrinking workforce is thwarting Xi’s efforts to boost domestic demand. Since he took over 2012, China’s working-age population—aged 16 to 59—has been declining. It dropped by nearly 7 million last year to 858 million, according to the Bank of Finland.

(3) It’s all connected. All this feeds into China’s 3Ds problem: deflation, debt, and demographics. Falling prices that take on a life of their own, local governments facing multi-trillion dollar debt burdens, and a fast-aging population each are challenging enough. China’s need to tackle them simultaneously explains why many see China growing around 2% at best by the 2030s.

Alicia García Herrero of investment bank Natixis warns China will “feel these effects more significantly after 2035,” when the economic boost of urbanization ends.

(4) So many men. China’s worsening sex ratio imbalance is another problem for population growth. A Mao-era side effect is a preference for having boys over girls. Because China lacks social safety nets, elderly parents move in with one of their sons’ families. Having girls is likened to “watering your neighbor’s garden” since wives end up caring for in-laws. In 2024, China’s gender imbalance reached at least 104 men to every 100 women.

China is already plagued by high youth unemployment. The social instability risks of whole generations of lonely young men are obvious enough.

All this means that falling prices risk deflating far more than just next year’s GDP.